Here at the Read House & Gardens our history comes in layers that reach all the way up to the present.

LIKE THE REST of Old New Castle, the 14,000-square-foot mansion built for George Read II and his family sits on land once known as Lenapehokink, traditional home of the Lenape people for tens of thousands of years. By the time plans for the house were underway in 1797, the town had passed through Swedish, Dutch, and British colonial control, and it was now the capital of the state of Delaware.

You can see everything from the roof—the Delaware Memorial Bridge to the North, Delaware City to the south, and Salem County (New Jersey) and its nuclear generating station silhouetted beyond. Cargo ships make their way up and down the Delaware River—a constant reminder of how water once connected this now-sleepy enclave to the world. In the Reads’ time, it brought goods, people, and building materials including those that made this house itself. Read’s brother William, a successful Philadelphia merchant once hailed as a “pioneer” in the opium trade with China, was among the many whose vessels stopped off in New Castle before making their way out to sea. During Prohibition in the 1920s, when Philip and Lydia Laird were living here and entertaining their many friends and relatives (both were tied into the extensive du Pont family), liquor seems to have floated in on boats and seaplanes to keep the fabulous Read House parties from going dry.

GEORGE READ, barely 32 when the cornerstone was laid, set out to build a grand mansion with the expectation that he would become an important statesman like his father, who had signed the Declaration of Independence and Constitution and served as governor, chief justice, and U.S. senator in Delaware. The younger Read served as Delaware’s first U.S. attorney for 27 years (and his son George III succeeded him for another 21), but he failed to gain traction politically. Nevertheless, he built a spectacular showpiece.

Our trove of family papers show Read obsessing over design, craftsmanship, and materials—and he was often financially overextended because of it. In order to have silver-plated door hardware, which was not readily available in America, he was willing to pay John Richardson in Philadelphia six times the usual cost to custom-plate the ordinary brass pieces. It took multiple tries to get them right.

“Read’s mansion in New Castle is a Philadelphia house, maybe even the best surviving example of domestic architecture from Philadelphia’s grand federal period.”

READ’S MANSION in New Castle is a Philadelphia house, maybe even the best surviving example of domestic architecture from Philadelphia’s grand federal period. It was built mostly by Philadelphia craftsmen, and many of the materials came down the river from there too. Read had spent enough time in the city to know the current architectural styles, but his brother John and brother-in-law Matthew Pearce lived there and acted as his agents. They gave input on design questions, made arrangements with tradespeople, and scouted out the best prices on building materials from mahogany to bricks.

If you walk around the Philadelphia neighborhoods of Society Hill and Old City today, you’ll see frontispieces (the decorative woodwork around entry doors) with motifs of grooves and holes that look a lot like the Read House. It's a style of decoration known as “punch and gouge” that originated in London in the 1770s but became hugely popular in the Philadelphia region around 1800. Read took it to a new level. Nearly every piece of woodwork in the main section of the house is covered in these surface carvings. In fact, no other house we know of in America or Britain has more punch-and-gouge work than the Read House.

Thanks to his contacts, Read worked with some of the best artisans. The house’s extraordinary ceiling plasterwork was done by William Thackara, the prolific plasterer responsible for Congress Hall in Philadelphia and the U.S. Capitol in Washington, among many other buildings. The ornamental designs on the mantles, which are molded out of a substance called “composition,” came from Robert Wellford, who was the go-to for composition ornament in Philadelphia’s elite interiors.

“Few of these people looked like the Reads or would have been welcomed as guests in their house, and some were almost certainly enslaved.”

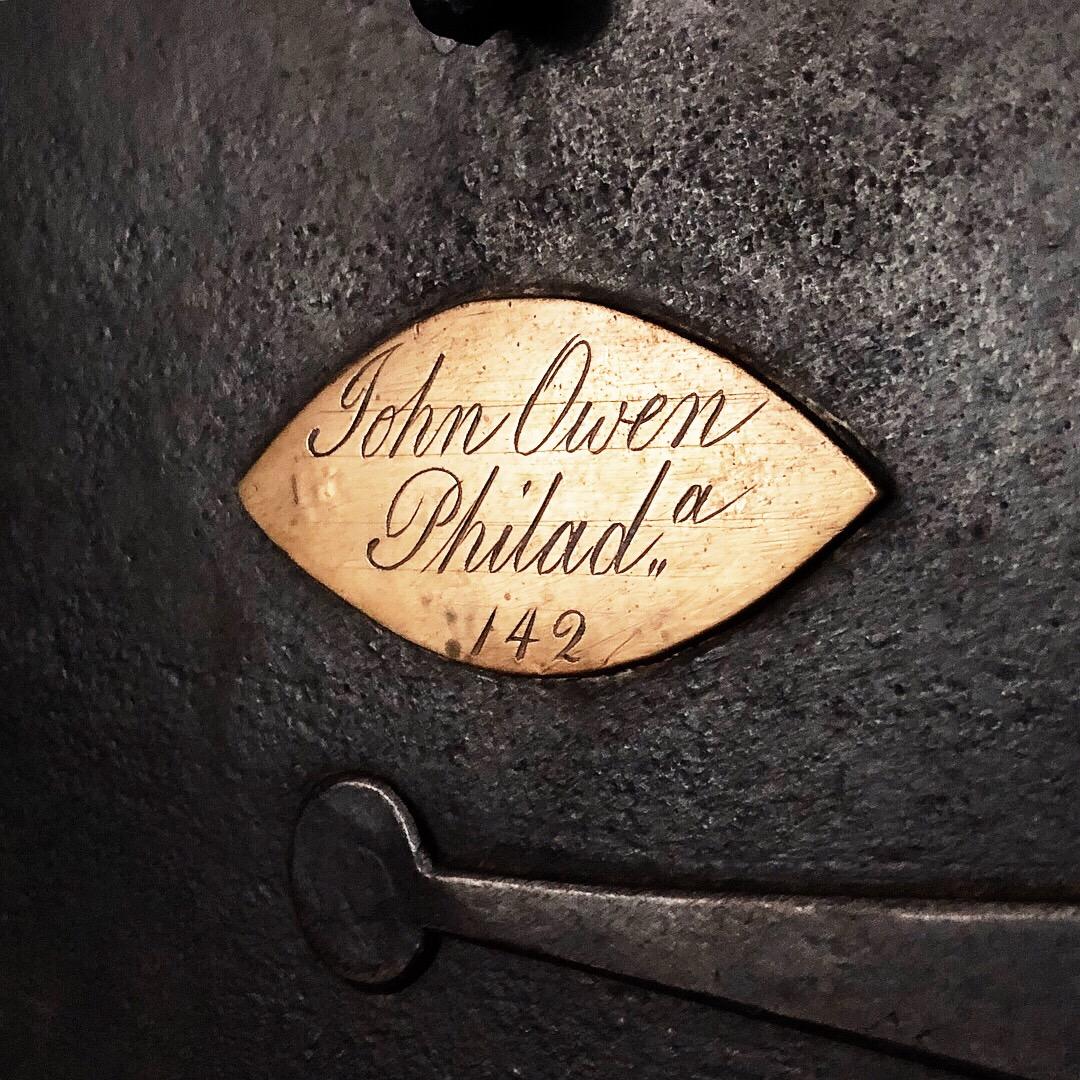

FROM THE MASONRY to the enormous mahogany doors to the cutting-edge kitchen technologies, the finished house leaves us with riddles to ponder about the lives these things touched. Who worked at the docks where bricks were loaded and unloaded? Who harvested the tropical mahogany, who hauled the timbers, and who sawed them into planks? Few of these people looked like the Reads or would have been welcome in their house, and some were almost certainly enslaved. Did George Read consult with a professional cook—like Sylvia Rice, the free African American woman who lived in New Castle later worked for the family—before having John Owen craft his fancy Rumford roasting oven? All the little vents that had to be regulated to keep from burning the food or wrecking the oven were notoriously a pain in the neck. The people who knew this were the women, often of color, who did the cooking.

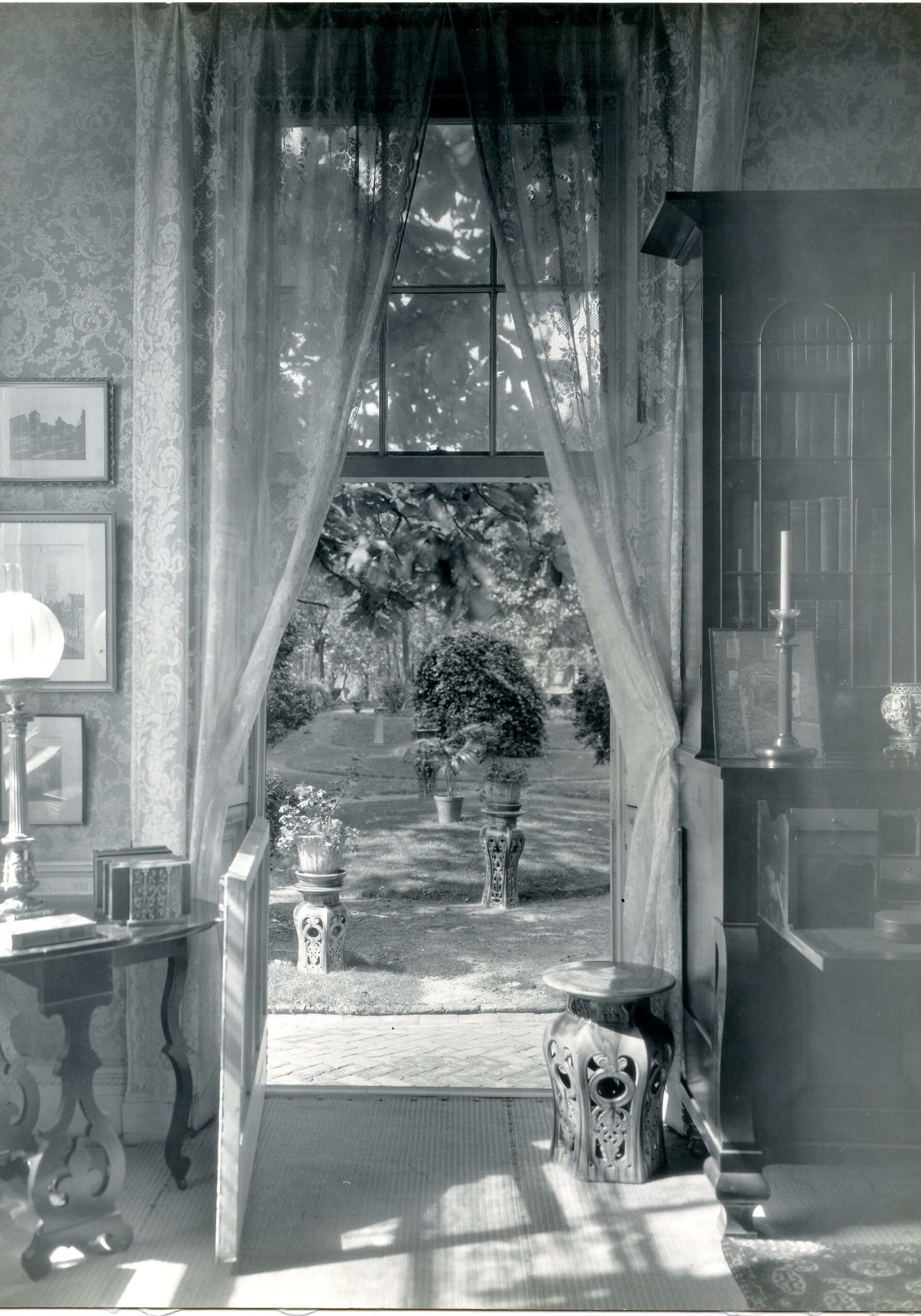

GEORGE READ II died in 1836, and by the time the house was sold out of the family in 1846, it was already a historic landmark of sorts. The buyer was William Couper, who had spent part of his childhood next door in the house of George Read I, which the younger Read rented out after his father’s death. Couper went off to make his fortune in the China trade—mostly tea, with a short stint in the lucrative opium game—and found himself in a position to snatch up the celebrated Read mansion when he returned. He shared the house with his mother, siblings, and their children, and over the 73 years it stayed in the Couper family they treated it with respect, making relatively few changes. Most of the updates were in the décor, like the Chinese lantern and ceramic vases you can see in early-1880s photos of the parlors.

The extensive gardens were Couper’s doing. Read seems to have been short on cash and gave up on landscaping the grounds, but Couper commissioned a well-known Philadelphia nurseryman named Robert Buist to lay out the gardens in three parts: a formal parterre garden beside the house, a naturalistic garden with specimen trees beyond it, and a kitchen garden in the back of the property. Individual plantings have had to be replaced over the years, but the layout of paths seems to have stuck, making this an important surviving example of a mid-19th-century urban garden from a time when most of the buzz in landscape design was about country gardens.

“The Lairds were preservationists, but they were designers too. . . . By decorating with antiques and having the rooms photographed for magazines, they were turning history into a question of taste.”

THE COLONIAL REVIVAL movement was in full swing when Philip D. Laird and Lydia Chichester Laird bought the house in 1920. New Castle was in a long slump, and the lapsed waterfront industries along the Strand didn’t look much like the elegant cobblestone-paved byway we know today. Buying up 10 other neighboring properties and helping to organize a townwide movement, the couple wanted to make New Castle a destination for historical tourism along the lines of the new Colonial Williamsburg. The Lairds were preservationists, but they were designers too. In the streetscape as well as inside the Read House, it was about creating a consciously historical look. By decorating with antiques and having the rooms photographed for magazines, they were turning history into a question of taste.

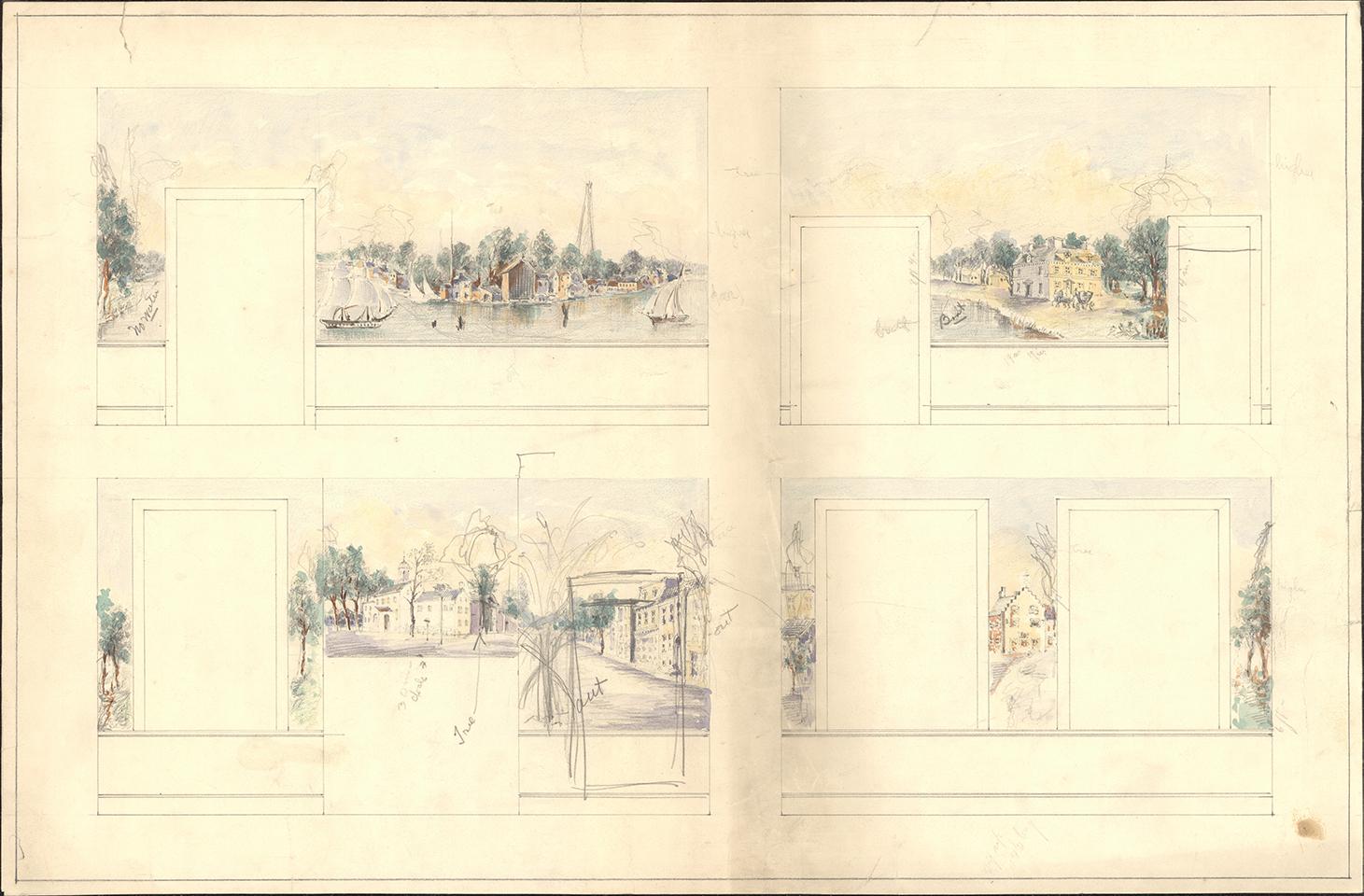

One of the most iconic photos of the house, taken by the noted woman photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston and published in Town & Country magazine in 1930, is of a made-up room. The Lairds’ dining room was initially George Read’s law office, and when it was, it had none of its present wallpaper or furnishings. The couple commissioned the wallpaper in 1927 to be hand-painted with scenes of New Castle history: the old courthouse, George Read I’s house, a long-lost Dutch house down the street, even a far-out scene of William Penn being greeted by Lenape residents upon first landing in America. Some high-style houses in the federal period had wallpapers with classical or exotic scenes. Some rural houses had local scenes painted directly onto the walls by folk muralists. But for the Lairds a century later, the luxury of fine wallpaper and the quaintness of local scenes were all part of one conglomerate “colonial” vibe.

Like their cousin Henry Francis du Pont at Winterthur, the Lairds wanted to set an example. Long before either Winterthur or the Read House reopened as a museum, their owners used them as semi-public showcases of good citizenship, where stewarding America’s past went hand-in-hand with cultivating certain aesthetic sensibilities. They were in good company. In 1924, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art opened “period rooms” in its new American Wing. At the same time, it was sponsoring annual exhibitions of household design that culminated with the 1927 Exposition of Art in Trade held inside R. H. Macy’s department store. The Read House was part of that axis of history and modern convenience. If you flip through magazines like Country Life, House & Garden, or House Beautiful, you’ll find pictures of the house mingled with advertisements for reproduction furniture, art deco bathroom fixtures, and sleek new automobiles. The colonial revival was about the past, but the people driving it lived unmistakably in the present.

“New Castle’s colonial-revival heyday in the 20th century was not favorable to everyone. It was a dream world, and the characters in it were usually white and affluent.”

LIKE MANY THINGS in our own time, New Castle’s colonial-revival heyday in the 20th century was not favorable to everyone. It was a dream world, and the characters in it were usually white and affluent. A writer for Country Life in 1920 imagined the town’s “powdered gentry…walking the shaded pavement in their leisurely journey down the Strand” each day, but in reality, the town’s inhabitants were more diverse than that when George Read I and II lived here. How do we confront this difficult legacy? When we cut people out of the past, we’re excluding them from the present.

“But years of white gloves and guided tours also make it easy to forget that this was a real house that was bought, sold, lived in, loved, and constantly evolving...not a space frozen in time.”

2020 marked a century since the Lairds took on the Read House and 45 years since Lydia Laird left it to the Delaware Historical Society. It’s been operating as a museum since 1976, and we’ve benefited from a lot of stellar research during that time. After careful investigation, a major restoration project in the 1980s reconstructed what many of the rooms might have looked like when the Read family lived here, which is what visitors see today. But years of white gloves and guided tours also make it easy to forget that this was a real house that was bought, sold, lived in, and constantly evolving—not a space frozen in time.

So with your feedback and support, we’re opening up a broad new conversation about what the Read House & Gardens should become as we head deeper into the 21st century. The dialogue isn’t just among curators anymore (although according to Elle, “a curator boyfriend was the hottest accessory for 2020...”). We’re talking with interior and fashion designers, photographers and magazine editors, even environmentalists. Most importantly, we’re talking with people like you—whoever you are and whatever your interests! From concerts to community gardening to our annual “LIT for the Holidays” bash with installations by artists from across America, we’re inviting you to come and chat and experiment with us as we explore new frontiers. So be sure to stay connected through our Instagram, Facebook page, and email list, where you’ll always hear what’s up next and where the conversation never stops.